When you read a Shakespeare play you’ll probably notice that it’s divided into acts and scenes – and always has a five act structure. The number of scenes in each act vary but there are always be five acts, no exceptions.

Why is that? Is there something about Shakespeare’s plays that made it necessary for him to divide them up in that way, into acts and scenes? The answer is no, not at all – there is nothing about them that calls for any division al all. And yet all Elizabethan and Jacobean plays, and in fact, most plays all the way up to and including the 20th century are structured in five acts.

The truth, certainly as far as Elizabethan and Jacobean plays are concerned, is that the playwrights did not write them in five acts – that division was done later by the various editors who worked on their plays. One can see the logic of the division, however.

As long ago as 350 BC Aristotle famously wrote that a play must have a beginning, a middle, and an end, which is the beginning of structure. In his work on dramatic theory – ‘Poetics’ – Aristotle examined scores of plays and set out his explanation of makes a play work for an audience. According to Aristotle a drama is action – it is all about the events of an individual’s life. It’s not about a character: it’s about the events that derive from character and the events that result from character. It’s not an imitation of character, then, but of life, which, according to Aristotle, consists of action.

According to Aristotle the beginning of a play consists of the presentation of a character, someone the audience can identify with. That is a beginning – an opening, a first act. The character makes a decision and performs an action, which moves the play on. That action has consequences, and so it goes on, until that initial action results in a climax, followed by a reversal and then a resolution. All that will make the audience hold its breath and then release it at the end in a kind of catharsis.

From that one can see a structure, which we still have in drama today – regardless of the number of acts used in print. Aristotle certainly did not divide the action into five sections. It was the Roman critic, Horace, three hundred years after Aristotle, who advocated that, and by the beginning of the first century in Rome it had become conventional. All Seneca’s plays were structured in five separate acts with musical interludes between them.

Shakespeare’s texts do not only have five acts and several scenes but each scene indicates the location of the action in that scene. Shakespeare did not do that, nor did he divide the plays into acts and scenes. All that was done for the first time by the playwright Nicholas Rowe (1674-1718), in his six volume edition of Shakespeare’s plays he edited in 1709.

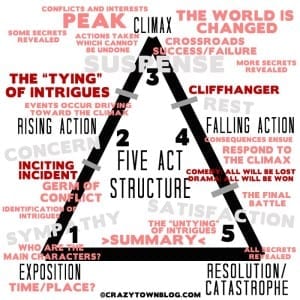

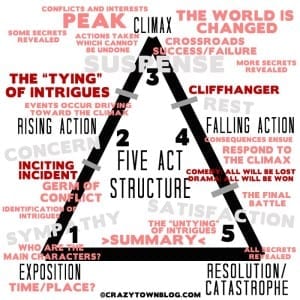

The German critic, Guystav Freytach (1816-1895), attempted to rationalise the five act structure. In his model the first act is the exposition, introducing the characters and the setting and ending with the play’s significant piece of action. The second act takes that action and complicates it: that’s the complication. In the third act there is a climax, where the fortunes of the character or characters are reversed – either good to bad or bad to worse: that’s the climax. In the fourth act the results of the reversal are played out, putting the final outcome in doubt. This is the resolution. The fifth act winds it all up by presenting the consequences of the resolution and tying up loose ends. That is the denuement.

Shakespeare’s plays do not exactly fit any pattern described by such analysis. They conform generally to the Aristotelian model but depart from that in the most wonderfully creative ways while still working for the audience. They also sometimes resemble Freytach’s scheme but do not fit neatly into it.

As a rule the division of Shakespeare’s plays into a five act structure is a meaningless nonsense. The plays are fluid and continuous and any divisions Shakespeare makes depend entirely on his own dramatic purpose. Editors divide Antony and Cleopatra into acts and scenes, for example, but the text does not lend itself to that. It moves very quickly to locations around the ancient world, mainly to-ing and fro-ing between Rome and Alexandria in short pieces of action. If Shakespeare came back he would laugh if he were to open a copy of one of his plays and see the division into acts, particularly if Antony and Cleopatra was that play.